Once again, in another of those occasions where great decisions have to be made, my father is, to all intents and purposes, submerged in the hinterland. I place the date at around 1915. I remember we were in the throes of World War 1, and it all comes back to me now.. .the graphic accounts of fighting soldiers. I have a vivid recollection of pictures of Russian Cossacks pulling heavy artillery knee deep through snow and slush. As a small boy, all this held me spellbound, and I simply failed to realize the full impact of a holocaust such as that was.

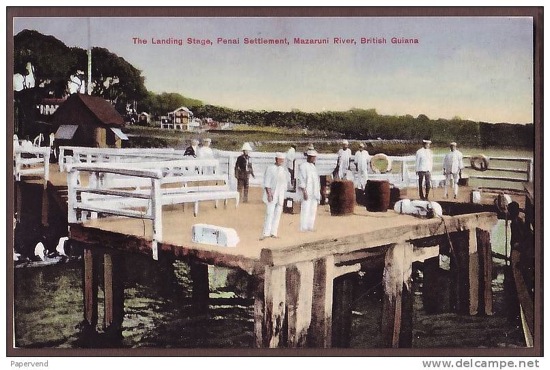

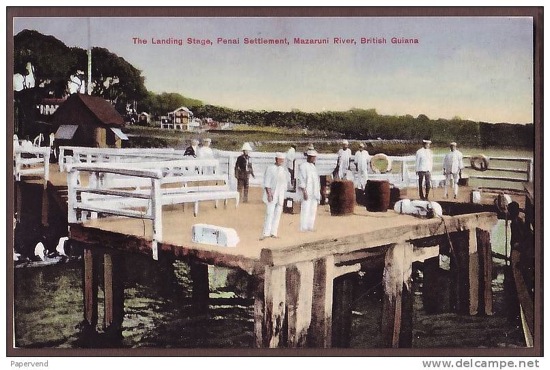

The only close relation we had at this time was my uncle Fred, the brother of my deceased mother. He was employed as a prison warder at a special institution for long term prisoners at His Majesty’s Penal Settlement, (H.M.P.S.). This place was located about one days’ travel from Georgetown by train and river steamer up the Mazaruni River at a paint just below “Kyk-Over-All” (look over all), a former Dutch fort which stood at a strategic position on a little island at the confluence of the Mazaruni and Cuyuni Rivers.

My uncle was married to my father’s daughter by his (my father’s) first wife, and although at first glance itwould appear that this was a family intermarriage, upon examination it was obvious this was not so. They had one son, Herbert. He was six years my senior, and the family lived in a small apartment at H.M.P.S.

My uncle and my half sister, his wife, were poor people, and my everlasting gratitude goes out to them for agreeing to take my three year old brother Frankie, my six year old sister Edna and myself, aged nine, to live with them in their humble home.

My elder brothers Jack and Eddie remained in Georgetown with friends. Jack was forced to leave college, and found employment at Garnett and Company, one of the prominent local firms then. Some years later at an early age, he got married, and he and his wife left the country for Trinidad. My other brother Eddie was encouraged to follow in my fathers footsteps and worked in the interior, in search of gold and diamonds. Several years later he was drowned in a boating accident, just off Cartabo Point.

And so, Frankie, Edna and I were thrown together in completely new surroundings, and here we spent many years of our lives in what I can only regard as one of the most important periods of our chequered existence.

His Majesty’s Penal Settlement (King George V was the reigning British monarch at the time) was the most unique place. As previously explained, only prisoners with long sentences were sent there and the situation of the settlement was ideally suited to discourage any attempt to escape from incarceration.

Built on a well-planned sloping bit of hilly terrain, it rose gradually from the river’s edge to the crest on which stood the prison, completely surrounded by a massive wail. Its location was on a curve of the Mazaruni River, so that a deep, almost mile-wide body of swift flowing amber coloured water bordered it on two sides, and virgin jungle on the remaining edges. In addition to this, the river was notorious for its Pirai fish, a voracious and attacking species of Piranha.

Escape via the jungle would have been extremely difficult as well, because it would have taken weeks of rough going through the tropical rainforest to reach any sort of civilized community. To penetrate the jungle, one would also have to run the gamut of flooded creeks and streams, venomous snakes like the Bushmaster and Labaria, in addition to avoiding brushes with pumas, wild hogs, and various creatures.

During the five years I lived at H.M.P.S., several prisoners made escape attempts, but to the best of my knowledge not one was ever successful in gaining his freedom. These attempts usually ended in recapture due to near starvation in the forest, or drowning in the river. I once saw from the window of our home, the outstretched arm of a prisoner rising above the water on the surface of the river and then disappear. When the body was recovered, it was found to be a case of suicide, since the body was weighted. The poor man must have given up all hope of ever being free again, and so decided upon ending it all in a watery grave.

As another instance of how secure the Government considered M.I.P.S., several Germans living in Georgetown, the Capital City of British Guiana, were sent up to this Convict Settlement for protective custody during the War years of 1914-1918. It must be recalled that during that period Britain was at war with Germany, and British Guiana was then a Crown Colony of his Majesty’s (George V) Empire.

One of the unique features of M.I.P.S. was the fact that it was almost self-supporting. When the convicts realized that escape was very difficult, they quickly settled down to a fairly peaceful performance of their several duties. The entire settlement was run like a miniature town. The whole outfit was a Government project, with the various amenities which go into the making of a self-contained community. As was expected to be, it was a completely restricted area, restricted to the personnel employed there, and their families. Friends and visitors were of course permitted to come and stay for a reasonable length of time, but Passes had to be procured from the authorities.

The number of Warders employed was approximately forty, and free houses were provided in four or five different locations on the settlement. Many fringe benefits were regularly supplied to the staff, such as a weekly supply of cut firewood, maintenance and cleaning of the grounds and area around the apartments and the daily removal and disposal of the chemical toilets and garbage. There was no sewerage or septic tank installation at that point in time. The prisoner count varied with the City crime, but an average of two hundred prisoners was always present. These convicts represented the entire labour force and were divided in various gangs in the carrying out of their allotted tasks. Many were skilled in various trades, to which they were best suited. The largest group was the farm gang; it comprised about forty prisoners, and about four warders were assigned to supervise this particular lot. I remember my uncle being in charge of this Farm Gang for quite a long time, since he had some previous experience of this vocation.

The Farm was principally livestock. The resident families were supplied daily with milk (fresh) of a delightful quality, and meat was also available about twice a week. Things like sweet potatoes, plantains, peas and vegetables of all sorts were also grown, and sold at reasonable prices to the homes. There was another group of prisoners referred to as the Forest Gang. These would cut timber in the adjacent forest, and pass it on to a small group who operated a small sawmill. The firewood supplied to the homes was also delivered by the Forest Gang.

Baking of bread was done every day by those of the prisoners with baking experience, and sold to us all, while small and select groups were engaged in an engineering shop, others in a granite quarry on the southern periphery of the settlement. The granite was blasted out of a solid large hill using sticks of dynamite and the stone was afterwards used to surface the roads, the surplus being shipped by barge to Georgetown, where it was also put to use on road-work. Every opportunity was used to make the place as self-supporting as possible, and it also served the useful purpose of keeping the convict community fully occupied.

There was a rather unusual feature at M.I.P.S. It possessed a Dry-Dock, in which all the Government river and coastal steamers were docked and repaired. The double water-tight gates of this dry-dock opened into the Mazaruni River and the ships which came for repair and painting steamed right into the open dock, when the double gates were closed; the enclosed water pumped back into the river, and the ships lowered gently onto the keel blocks at the base. In this manner the entire hull of the vessel became exposed, and repair and painting quite easily done.

It was always a thrill for us children to see this operation in progress, and between repair jobs, the dock proved to be a very good swimming place. It was there, with the aid of a large floating plank of wood and some willing friends that I really acquired the art and ability to swim.

The penal settlement was managed by a superintendent of prisons, and during the time I lived there, this august person was Harold Frere, afterwards Sir Harold Frere. The name was obviously French in origin, and he later married the daughter of Sir John Harrison, who at that time was Director of Agriculture in Georgetown. There was also an assistant Superintendent - N.M. King. They both lived in great mansions surrounded by beautifully landscaped gardens, all kept in apple-pie order by prison labour. Each of these gentlemen had a tennis court on a portion of his grounds. The Superintendent, Harold Frere, was a great lover of motor boats, and kept two such crafts, one of which, a covered speed-boat, very sleek and trim, was named “Hecuba”. It was a real delight to see it skim ever so gracefully over the surface of the river. The other was a rather large two-decked Cabin cruiser named “Ducalion”, in which he and his party would go on longer trips up or down river for pleasure. So much for the top brass.

As young children, we would enjoy hanging around the main gate of the prison enclosure, and through the rail watch the Warders on afternoon parade as they emptied their six-shooter revolvers of bullets, taking home only the empty weapons, but leaving the ammunition in the safe keeping of the prison. All in all, even though we were in poor circumstances, eking out a meagre existence, life was not at all uninteresting.

My sister, my brother and I all attended the local school. In a small community such as this, the pupils hardly exceeded forty. The head-master was a short stocky person named J.A. Sobers, and his two assistants were his wife, and a younger man whose name was Lewis. There we were taught the basic 3 M’s, and just as much as a tiny country school could provide. It was a great step down from Sharples school in Georgetown, but we were content. There was a fair amount of organized recreation, and in this respect, just a couple of hundred yards from our home, was a large sports field which was kept pretty well manicured by prison labour. Field athletics were regularly organized here, and very often invitations would be sent to the city of Georgetown, and athletes would travel up to M.I.P.S. to take part in sports, adding both interest to the events, and providing the necessary competitive element so essential to all sport.

During my life in this country setting, I became a Boy Scout. Lewis, the assistant teacher at our school, organized a troupe, and so, at about the age of twelve, a completely new dimension crept into my life. Scout craft proved to be great fun, and in our particular location, close to both forest and river, we had an excellent opportunity really to extend ourselves.

On one of our scouting forays through the forest, a labba was shot by our scoutmaster, and I volunteered with another boy, to cook this delicacy. I ought to explain that a Labba is a much sought after rodent when hunters go a-hunting. It is somewhat like a rabbit in size, and is regarded as one of the tastiest of bush-meats.

Part of the system adopted at M.I.P.S. was to encourage self-support, and in this respect, large garden plots were allocated to the families. I have no doubt that this really started me off in my love for gardening. Between my uncle and myself we grew, or tried to grow, everything possible under the sun, from peanuts to potatoes. We did produce beautiful crops of sweet potatoes, peas, cassava, bananas and a wide variety of vegetables and greens. This certainly proved to be a welcome addition to our larder, and even if I might sound like bragging, we really made a success of our home garden.

The health of the population of M.I.P.S. was taken care of by a resident G.M.O. (Government Medical Officer) and a couple of trained Dispensers. A dispenser was a sort of doctor’s aid, and by virtue of this it was he who did little things like minor surgery, such as lancing and draining an abscess I once developed. Simple teeth extraction was also done by him.

By one of those strange quirks of fate, one of the doctors stationed at the Settlement while I was a boy there was Dr. D.J. Taitt. Dr. Taitt, Jabez to me now, is still alive. He is the widower of my wife’s sister, Dorothy.

The spiritual needs of the populace were taken core of by am Anglican minister, whose name I recall was Rev. Papworth. There was a chapel within the prison walls, in which he conducted religious services for the prisoners, using another building near to the schoolroom for the general public.

There was a canteen where food and other items were purchased. It would be a supermarket by today’s standards, and it was operated by individuals under some kind of franchise from the government. Items not available here were ordered from Georgetown, and my uncle dealt with the once famous firm of Smith Brothers and Co. Once a month a box of our special supplies would arrive by steamer, and the opening of it would be quite an event.

There was a twice-weekly steamer service from Georgetown. The trip took almost a whole day, leaving the city which is situated on the Demerara river at six a.m. heading out into the Atlantic ocean for a couple of hours, then entering the Essequibo river at Parika, afterwards proceeding for several hours until the Essequibo met the Mazaruni river. The situation of M.I.P.S. was no more than about forty minutes by steamer from this meeting of the two rivers, Essequibo and Mazaruni.

It is impossible to say how long this convict colony existed before my advent there, but it was easy to see from the type of buildings there, several of which were made of hewn square stone, the rugged walls, and the general layout of the place, that the Dutch may have started all that work before the British came into possession.

Along the well kept roads which wound and curved gently around the hill, H.M.P.S. was in reality a giant size hill sloping away to level land where it reached the jungle edges) there were dozens of Mango trees of every possible variety. These trees were all within easy walking distance of the homes, and it was great fun to wake up at the crack of down, carry the biggest basket one could find, and fill it full of the most succulent fruit which had fallen during the night. My favourite species was the Ceylon type mango. It was a large orange-shaped fruit with a thin pale skin, an aromatic and spicy meat inside, and a very small seed. There was a single tree which bore this type of fruit, and it was near to the prison gate. For many many months, this particular tree was the home of a two-toed sloth, and perhaps this fact made the tree all the more famous.

How could I ever forget the fishing we enjoyed in the small ponds and trenches in the “back dam”. We had a special method of catching fish, without rods or honks or any of the orthodox paraphernalia. Our gear would be a couple of pails, shovels, a few bits of wood and a piece of fine chicken wire. Selecting a long and narrow trench in which we had proved there were fish, we would block off one end and set up the chicken wire at the other. Since the terrain tended to slope somewhat, with a little encouragement, we would help to drain the water away, trapping the fish in the blocked part of the trench. Very often we had to use the pails to bale out the last of the water before collecting the fish.

When my sister Edna, my brother Frankie and I left our Cummings Street residence following the death of our guardian, Mrs. Mc Allister, and went to live with our uncle at H.M.P.S., the three of us were still quite young. We really enjoyed the change of scenery, and the new environment in this truly country setting. Those were the days before Radio and Television, and as a result, one’s entertainment took on a completely different aspect to that enjoyed today.

My uncle was an extremely good raconteur, and I could recall his specialty of giving graphic and detailed accounts of the various works of fiction he had read. We would all go visiting friends on an evening, and he would spend a couple of hours relating to his spell-bound audience the complete novels he loved so well. Some of his favourites were, “The Count of Monte Cristo”, “Beulah” and many of Dumas’ works and Marie Corelli‘s. He certainly had a dramatic way that easily captured our attention and respect.

There was also another side to my uncle’s disposition; he had a violent temper and although he seldom vented it on the three of us - Edna, Frankie or myself - the worst flogging of my life was administered by him when a gold watch and chain, belonging to my half-sister, his wife, was missing. For some unknown reason, he concluded that either my brother Frankie or I was responsible for its loss, and decided to extract am admission from one or both of us. Using a leather belt, he lashed our bare backs for quite some time, but since neither of us knew anything of the watch’s disappearance, we just told him so. Frankie was a full six years younger than I, and in an effort mainly to save him from further agony, I told my uncle I had tossed the watch into a nearby Canal after I had damaged it. Although this stopped him beating my brother, it increased his attention to me until it finally stopped. It was not until many years later, when I was about 18 years old and working, did I discover that the real culprit was a servant who was then working for us and who lived in on the premises.

There were dozens of other memories I could recall, and looking back over the years spent in this environment, I hove to admit that in spite of the poverty in which we lived, we somehow contrived to enjoy ourselves. Once again, and in all sincerity, I wish to express my undying gratitude to my uncle and his wife for giving us the opportunity of being a part of their immediate family, .at a time when we most needed someone to take care of us.